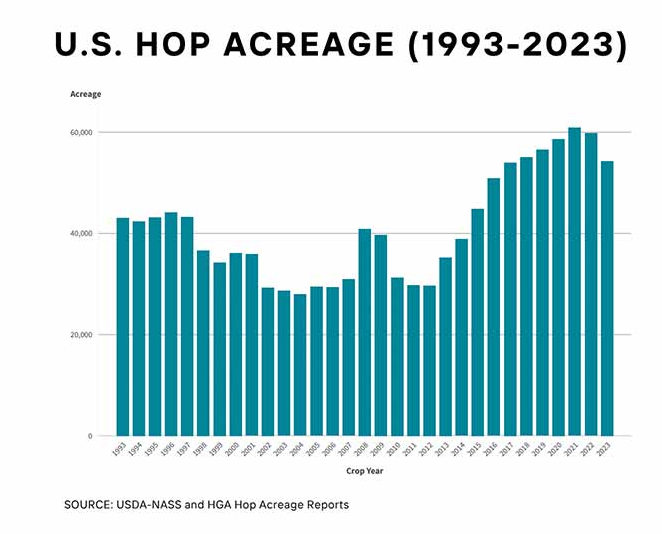

The total acreage farmers dedicated to hops is down this year. In this post, I will provide some exact numbers and insight into the reasons for this decline. I hope to convey a sense of calm reflection. Although it is not good news, it is not dire, “the sky is falling” news either. The reason may not be what you’re expecting.

Germany has just regained its position as the top hop-producing nation on earth. The U.S. held that distinction for the past nine years. Some other regions of the world produce hops, like New Zealand and South Africa, but the overwhelming majority of the world’s hop supply comes from Germany and the USA.

So how did Germany regain the lead? It is because of a decline in overall hop acreage in both countries, with the U.S. showing a greater decrease in acreage. In Germany, acreage decreased by 340 hectares to 20,300 hectares. In the U.S., acreage decreased by 4,500 hectares to 17,850 hectares. Those numbers were provided by the German Hop Growers Association.

According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, hop acreage strung in the U.S. for 2024 is forecast at 44,543 acres, down 18 percent from last year’s total of 54,318 acres. In Washington, the nation’s top hop-growing state, 32,982 acres were strung for harvest, down 15 percent from the previous season. In Idaho, down 31 percent from 2023. In Oregon, down 18 percent compared to last season.

The top five hop varieties strung for harvest in the United States this year are Citra, CTZ, Mosaic, Simcoe, and Cascade. These five varieties account for 50 percent of the total U.S. acreage strung for harvest.

The Law of Hop Supply and Demand

So, why has hop acreage declined in both nations? Why was the decline more profound in the U.S.? The amount of acreage farmers dedicate to hops each year is based on a few different factors, but it all comes down to supply and demand. In the U.S. there is currently a surplus of hops. Before you blame the surplus entirely on the much-reported global decline in beer sales, recognize that some other factors are involved, too. I am not dismissing the impact of declining beer sales; I’m just saying that is only part of the story.

I can only speak to the situation here in the USA, but the hop farmers created the surplus themselves. You could say that they over-planted in recent years. I think that’s what they’d say too. They were optimistic and responded to the general increased popularity of craft beer, which has now slowed. More specifically, farmers hedged their bets on the continuing popularity of super-hopped beers like hazy IPAs, which require brewers to use a lot of hops, as measured in pounds per barrel. Not just large quantities, but large quantities of the kinds of hops we grow in the U.S. You don’t see many hazy IPAs that feature traditional German hops like Hallertau or Tettnanger. Instead, hazy IPAs are packed full of fruity, tropical, dank flavors from more modern hop varieties like the ones we grow here in the States–Citra, Mosaic, and Simcoe for instance.

The Brewers Association reported that between 2010 and 2018, the average amount of hops per barrel used by its members grew by 50%, from 1.05 pounds to 1.58 pounds. Not coincidentally, this rise happened as hazy IPA gained nationwide popularity. It’s not uncommon for a beer of that style to use 5 pounds (or more) of hops per barrel. For a hazy IPA, the average is probably between 3 and 5 pounds per barrel. Other notably hoppy beer styles, like Italian-style pilsner, might require just 1.5 to 3 pounds of hops per barrel.

Things were weird and unpredictable in the years following 2018, but one thing seemed clear: hazy IPA was still popular. As any beer enthusiast has noticed, the haze craze has subsided, especially in the past two years. You’ll still find plenty of hazy IPAs and other hop-heavy brews on the shelf, but craft-brewed lagers and other less-hoppy beers have become much more common.*

In summary, the surplus of hops led to falling prices, which worries hop suppliers. With lots of hops in the cold storage warehouses, where hops can remain viable for up to five years, farmers have slowed their roll by decreasing the number of acres they dedicate to hops. It’s a period of adjustment. Over the decades, this kind of rollercoaster ride is not uncommon in the hop-growing industry. Another constant, nobody knows what the future holds. Will acreage increase again in the coming years? We’ll see.

Hop Industry Structure

Beyond all of that, one of the reasons Germany has overtaken the U.S. in hop production involves how the industry differs between the two countries. On both sides of the pond, the hop industry relies largely on contracts. Breweries sign contracts with the hop suppliers to establish pricing and guarantee availability for the coming years. According to the German Hop Growers Association, hop contracts in the U.S. are easier to manipulate and even cancel, so breweries can more easily reduce the size of their hop orders. To be fair, I know plenty of brewers in the U.S. who would tell you there is nothing easy about hop contracts.

Also, hop farming is structured differently in the two countries. In the U.S. you’ll find much larger farms. In Germany, you’ll find smaller, family-run farms. At any one moment, the larger farms have more to lose and need to pivot quickly to address changes in the market, especially since they are often funded by nervous bankers. German farms are more likely to be family-funded, to be governed by tradition, and to not give in to market pressures as easily.

Getting back to the impact of declining beer sales on hop acreage. That has less to do with sagging craft beer sales and more to do with the troubles that mega breweries are enduring these days. Although it might not taste like it to a crafty hophead, there actually are hops in Bud Light.

* Side note. If the world decided that it no longer fancied hazy IPA, many brewers would breathe a sigh of relief. Hops are a hugely expensive part of the recipe and that’s just one reason why hazy IPA is a notoriously expensive style of beer to produce. The brewery cannot pass that higher cost on to the consumer without inviting outrage.